© YOAN VALAT / EPA/MAXPPP

En octobre dernier, une militante d’Extinction Rebellion fait irruption dans un défilé de la Fashion week de Paris, avec une affiche sur laquelle on peut lire “Overconsumption = extinction” (surconsommation = extinction). L’opération dénonce l’impact de l’industrie de la mode, qui produit 8 à 10% des émissions mondiales de CO2 par an, sur le changement climatique. Malgré un constat écologique et éthique dramatique, nous sommes encore nombreux·ses à acheter des vêtements issus de la fast fashion. Pourquoi est-ce si difficile de renoncer à cette habitude de consommation ?

« Une fois que vous voyez à quel point il est difficile de confectionner des vêtements, le temps et l’effort que cela demande, vous comprenez que ce n’est juste pas possible qu’un t-shirt coûte seulement 5 euros. »

Wanda Wollinksy, Allemande de 31 ans, est créatrice de mode et co-fondatrice de la marque éco-responsable Kasia Kucharska. Avant ses études à l’Université des arts de Berlin, elle achetait beaucoup de vêtements fast fashion « parce que ce n’est pas cher, et quand on est jeune on n’a pas beaucoup d’argent ». Elle explique qu’au début de son cursus, c’était une façon de défendre la démocratisation de l’accès à la mode. Aujourd’hui, forte de son expérience, elle n’est plus aussi convaincue par cet argument et achète seulement des vêtements de seconde main.

La quantité de vêtements que représente la mode éphémère est ce qui rebute le plus la jeune femme.

«La plupart de ces habits ne sont pas biodégradables. C’est alarmant de penser qu’ils continueront d’exister même après ma mort», remarque-t-elle.

Les cofondateur·ices de la marque, de gauche à droite, Reiner Törner, Wanda Wollinsky et Kasia Kucharska. © Laura Schaeffer

Le paradoxe de la fast fashion

Pourtant la fast fashion cartonne, même quand ses pratiques entrent en contradiction avec les convictions écologiques des consommateur·ices. Bien que le changement climatique représente une préoccupation majeure à travers le monde, les ventes de vêtements jetables ont connu une hausse spectaculaire ces dernières années. Entre 2000 et 2014, la production mondiale de vêtements a doublé. En parallèle, le nombre de fois qu’un habit est porté a considérablement diminué.

Qu’est-ce qui explique ce paradoxe? L’experte Valérie Guillard affirme que c’est parce que « acheter, c’est gratifiant ». Professeure de marketing à l’université Paris-Dauphine, et autrice, entre autres, du livre intitulé « Du gaspillage à la sobriété : Avoir moins et vivre mieux ? » (De Boeck Ed. 2019), ses recherches portent notamment sur la psychologie et les pratiques des consommateur·ices.

« Quand on achète quelque chose, c’est un plaisir. Surtout quand il s’agit de vêtements, on se dit qu’on va être plus joli, qu’on va avoir quelque chose de nouveau à montrer. Et puis quand vous pouvez consommer quelque chose, ça veut dire que vous êtes en lien avec la société, car celle-ci valorise justement la consommation. De plus, la fast fashion n’est pas chère, ce qui permet à de nombreuses catégories sociales d’avoir ce plaisir. Renoncer à cela, c’est renoncer d’une certaine façon d’être par rapport à la société. »

Valérie Guillard précise qu’une habitude, c’est long à changer. Le caractère identitaire des habits rend la tâche encore plus difficile :

« Le vêtement c’est une identité, c’est l’exposition de soi à autrui et le regard d’autrui compte beaucoup – c’est normal, nous sommes en société ».

Dans ce cadre, renoncer à cette habitude de consommation peut être vécu comme une privation.

L’accessibilité de la fast fashion entre également en ligne de compte. C’est d’ailleurs même l’atout principal de ce segment de l’industrie vestimentaire pour Kartik Chawla, candidat au doctorat de 27 ans, qui se rend chez H&M ou Zara environ tous les 3 mois. Le jeune homme affirme acheter de nouveaux vêtements seulement en fonction de ses besoins saisonniers. Cependant, il explique qu’aller en friperie n’est pas une alternative pratique, car il n’a pas beaucoup d’énergie à consacrer au shopping en raison de son occupation professionnelle :

«J’ai essayé d’acheter des habits de seconde main, mais cela demande du temps et de l’effort additionnels de trouver le bon vêtement et de s’assurer qu’il soit bien ajusté à votre taille. Il se peut que vous ne trouviez pas votre compte dans le premier magasin, donc il faut aller dans le suivant, et ainsi de suite… Vous devez partir à la chasse aux habits.»

Kartik Chawla, 27 ans

Consommer une marque de fast fashion est alors davantage une question de commodité. Kartik dit être prêt à payer un peu plus pour un vêtement éco-responsable et éthique.

« Si j’avais connaissance d’une telle marque située près de chez moi et qui correspondrait à mes préférences en matière de style – un style qui vous représente, c’est important -, je m’y rendrais plutôt que d’aller chez Zara », précise-t-il.

Micro-tendances et réseaux sociaux : le duo infernal

Dans la fast fashion, le mot clé est fast – c’est-à-dire la vitesse à laquelle de nouveaux vêtements sont fabriqués et arrivent sur le marché. Alors que les marques haut de gamme sortent deux collections par année (automne et printemps), les entreprises de fast fashion telles que Zara proposent de nouveaux styles et tendances jusqu’à deux fois par semaine. Dans le cas du détaillant chinois de mode en ligne Shein, la période de conception et de production se réduit parfois même à 3 jours seulement ! Résultat : les consommateur·ices sont incité·e·s à acheter régulièrement de peur de manquer. Et puis les vêtements sont si bon marché que vous pouvez facilement justifier un achat impulsif et avoir l’impression de faire des économies.

La vitesse effrénée de la mode jetable a eu un impact sur la façon dont la marque Kasia Kucharska a abordé son propre rythme de travail au début de leur aventure. Wanda dénonce une pression auto-imposée :

« Cela fait environ deux ans que nous travaillons sur nos vêtements, et même si la plupart des gens n’ont même pas encore vu nos designs, on a l’impression que ce que l’on fait est déjà vieux et qu’on doit proposer quelque chose de nouveau tous les six mois de peur qu’on nous oublie ».

Face à cette cadence folle, elle défend la slow fashion et ses pratiques plus réfléchies et plus respectueuses de la chaîne de production.

Dessous de la marque Kasia Kucharska entièrement confectionnés en latex et biodégradables © Sandra Gramm

Le phénomène des micro-tendances est accéléré par les réseaux sociaux. Aujourd’hui plus de la moitié des publications sur Instagram sont consacrées à la mode ou à la beauté. Les marques de fast fashion délaissent la publicité traditionnelle pour se consacrer à un marketing plus subtil et plus ciblé avec l’aide d’influenceur·euses. À travers des vidéos de « haul », les créateur·ices de contenu fabriquent une relation plus « authentique » avec les utilisateur·ices, comme démontré dans le documentaire Arte, Fast Fashion – Les dessous de la mode à bas prix.

Marie Cherasse, Française de 26 ans, dit se limiter à des achats nécessaires mais reconnaît que les réseaux sociaux agissent comme une pression extérieure «sans que l’on s’en rende compte». Elle se remémore par exemple la mode du top Bardot :

«Je le voyais en permanence sur les réseaux sociaux, et à force de le voir porté, j’ai trouvé cela beau. Je me suis retrouvée en magasin avec l’envie de l’acheter».

Finalement, elle a renoncé à cet achat. L’empreinte écologique «ignoble» et les mauvaises conditions de travail derrière la fabrication de ces vêtements fast fashion ont motivé sa démarche et elle s’est aujourd’hui interdite d’aller dans des magasins tels que Mango ou Stradivarius.

« Ce n’est pas tenable de se dire que juste pour un t-shirt que l’on met en soirée, il y a des personnes qui vont souffrir de problèmes de santé graves ou qui vont mourir à 23 ans d’un cancer », remarque-t-elle, avant d’ajouter : « j’essaie d’acheter moins tout court ».

Marie Cherasse, doctorante en physique de la matière condensée, portant des vêtements de la marque éco-responsable Salut Beauté.

C’est pourquoi quand Marie a été contactée par la marque éco-friendly Salut Beauté pour être leur ambassadrice sur Instagram, elle a hésité avant d’accepter. Elle ne voulait absolument pas inciter à la consommation, mais au final elle s’est dit que promouvoir une marque qui utilise des tissus recyclés et a une stratégie marketing basée sur le féminisme est une manière de mettre en avant des alternatives qui peuvent pousser son entourage à réfléchir à leur manière de consommer.

La créatrice de mode Wanda Wollinsky ne peut que constater le pouvoir des réseaux sociaux pour sa marque de slow fashion. Leur page Instagram est leur principale forme de communication en dehors de leur site internet et peut s’avérer être un outil de marketing redoutable :

« Lorsque qu’une personne avec une grande plateforme poste une photo de nos vêtements et nous met en lien, nous obtenons soudainement 200 nouveaux followers et parfois quelques ventes. On en profite aussi ».

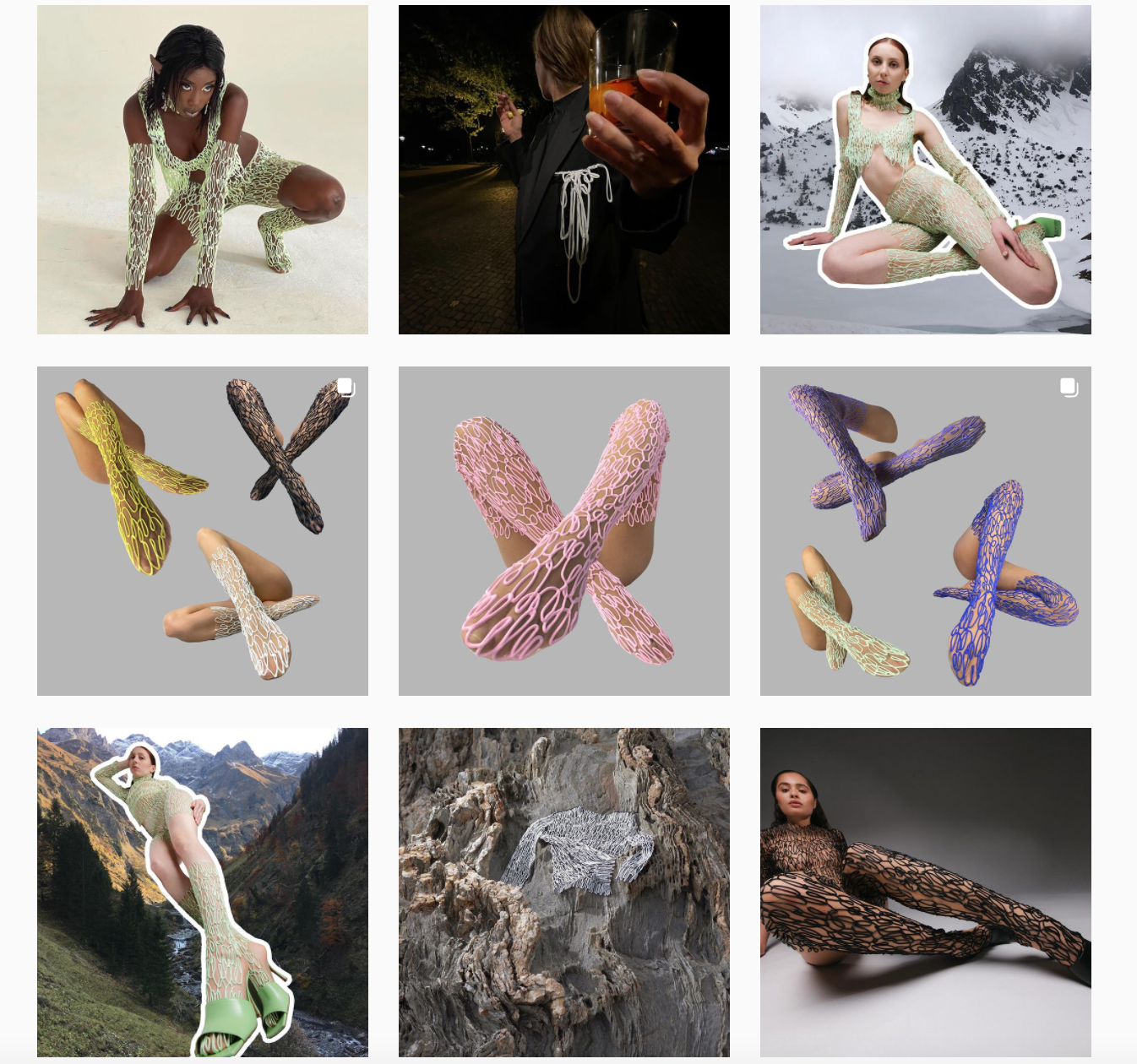

© Page Insatgram de Kasia Kucharska

L’experte Valérie Guillard note qu’il faut faire preuve d’une bonne capacité de discernement sur les réseaux sociaux qui peuvent s’avérer être très intrusifs et addictifs. Pour elle, une manière définitive d’échapper aux sollicitations et de simplement ne pas y être. Elle nuance toutefois son propos en précisant que « tout n’est pas à jeter » sur les réseaux sociaux.

« On peut aussi y trouver de l’aide et de bons conseils. Par exemple, si vous commencez une démarche zéro déchets, c’est intéressant de pouvoir rejoindre une communauté de personnes qui ont les mêmes aspirations que vous et qui vont vous aider à enclencher des changements de pratiques. On a besoin de modèles et de se sentir soutenu », souligne-t-elle.

Frénésie consumériste : que faire?

Piles de vêtements usagés jetés dans le désert d’Atacama au Chili © MARTIN BERNETTI / AFP / Getty Images

En novembre dernier, on découvre dans les médias des images surprenantes dévoilant des montagnes de textiles usagés s’étendant à perte de vue dans le désert chilien. Ce type de décharge à ciel ouvert, que l’on peut également trouver au Ghana, en Inde ou encore en Côte d’Ivoire, apparaît dans notre fil d’actualités plus ou moins régulièrement.

En 2013, c’est l’effondrement du Rana Plaza qui abritait plusieurs ateliers de confection textile et a provoqué la mort d’au moins 1 138 personnes qui marque les esprits.

Les images et événements faisant étalage d’une certaine frénésie consumériste et de ses conséquences catastrophiques ne manquent pas. Il est difficile dès lors de parler d’un déficit d’information au sujet de la fast fashion. « Mais l’information est-elle conscientisée ? » interroge Valérie Guillard. Elle explique qu’il est nécessaire de prendre du recul et de comprendre où on se situe par rapport à cette problématique.

Certains déplorent le greenwashing des marques et la confusion que cela peut provoquer. Kartik Chawla se méfie par exemple des étiquettes de vêtements indiquant une fabrication durable ou avec 100% de matériaux recyclés :

«Parfois je reviens en arrière et tente de vérifier ces données, mais c’est un effort supplémentaire. Il peut y avoir beaucoup de choses en arrière-plan dont vous n’êtes tout simplement pas au courant».

© H&M

Marie Cherasse dit s’être imposée une démarche dans laquelle elle vérifie systématiquement si un vêtement est éco-responsable :

« C’est un peu lourd pour le cerveau quand tu es exposé chaque jour à des offres attractives et qu’il y a une envie qui s’éveille dans ton esprit. Quand je vois que l’habit ne correspond pas à mes critères, ça peut parfois être un peu déprimant ».

La professeure Valérie Guillard estime toutefois qu’être en cohérence avec ses valeurs peut amener un sentiment de bien-être.

« Du moment qu’on a intégré les valeurs de la sobriété, on déplace la norme et ça peut nous apporter une vraie satisfaction », note-t-elle.

Acheter moins mais mieux pourrait donc être une solution, mais l’experte prévient des dangers d’un discours excluant envers certaines catégories sociales et précise qu’il est important de distinguer entre « celleux qui ont un pouvoir d’achat et qui peuvent substituer la qualité par la quantité et celleux qui ne peuvent pas ».

Wanda, pour sa part, rappelle que la quête stylistique peut continuer à être une expérience agréable pour les consommateur·ices et qu’on peut faire des friperies et des boutiques de seconde main son nouveau mantra. « La mode, c’est fun ! » s’exclame-t-elle.

Si vous souhaitez approfondir ce sujet ou d’autres, le réseau social La Mèche contient une médiathèque qui recense un grand nombre de ressources pour vous aider au quotidien à trouver des réponses à vos questions, des solutions pratiques et des idées pour adapter votre style de vie et vos pratiques aux enjeux d’aujourd’hui. De très nombreux sujets sont traités tels que la mode, l’alimentation, la maison, le business et bien d’autres encore.