A few years ago, on the occasion of a collaborative project between London’s Central Saint Martins University and the watch brand we’d just created, with the idea of inspiring a more sustainable and responsible vision of the industry, a student literally scotched me by posting a very simple question: “But if you want to preserve the planet, why have you created a new brand that uses resources and pollutes?” The logic is implacable, even if it can be argued that pioneering brands can play a locomotive role in driving change.

The simplicity of this question is enough to highlight the inconsistency of the carbon neutrality claims we’ve been seeing in brand communications for some time now, and some of them are not without their salt. Among them, we particularly appreciated the carbon neutrality of the soccer World Cup in Qatar and EasyJet’s zero CO2 emission flights by 2050. No, carbon neutrality cannot be achieved at brand level. Any organization that tries to make you believe this is engaging in greenwashing and helping to sweep the real issues under the carpet.

What do we mean by carbon neutrality?

According to the IPCC Special Report 2018 “carbon neutrality is achieved when anthropogenic CO2 emissions are balanced on a global scale by anthropogenic CO2 removals over a given period”. In fact, to be more precise, we need to aim for neutrality in emissions of all greenhouse gases (GHGs) emitted by human activity (CO2, methane, nitrous oxide and others).

First of all, carbon neutrality cannot be envisaged at company level, but must be considered at global level. CO2 is a GHG with a cumulative effect, and today’s emissions will disrupt tomorrow’s climate. So we can’t claim to have achieved carbon neutrality by planting trees that will only absorb CO2 in decades, and store it only if the project is viable (I’ll come back to this). On the other hand, the company would have to prove that its net CO2 emissions have been zero since the beginning of its activity, which is impossible. The aim is to do all we can to help reverse a global trend. Corporate carbon neutrality can only be achieved when it is achieved on a global scale. Of course, we need to encourage individual and collective action, even on a small scale, but we also urgently need to encourage socio-economic players to change the way they talk, because communicating about one’s contribution to a global effort to achieve carbon neutrality is quite different and does not have the same consequences as claiming to have achieved carbon neutrality.

There are four possible explanations for a company’s “carbon neutrality”:

-The first is the absence of greenhouse gas emissions, whether direct (scope 1) or indirect (scopes 2 & 3).

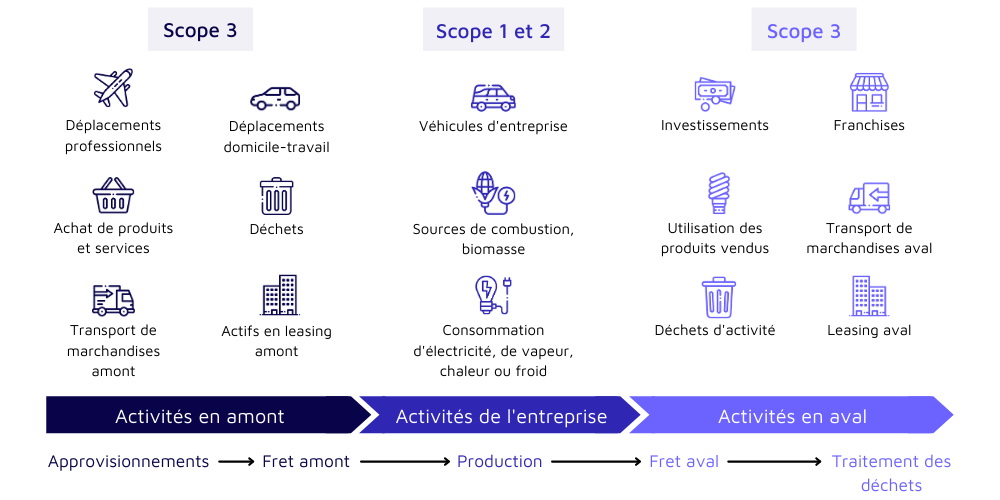

Here’s an excellent infographic by Carbo to help you understand what we’re talking about:

To generate sales, a company has to sell products or services that require the use of materials and components. It has to employ people to produce, deliver services, transport and sell, and these people have to travel. All these activities emit greenhouse gases. The first sleight of hand used by some companies is to focus exclusively on the first 2 scopes, thus considerably lightening their balance sheet, since scope 3 represents over 80% of emissions for the vast majority of companies. As you can see, the only way to reduce emissions or emit nothing in this case is to produce less or nothing at all. This brings us back to my student’s question.

-In the second case, the company’s products and services save as much or more GHG as it emits. One example is a company in the energy sector that installs heat pumps in place of oil-fired power plants. However, the vast majority of companies are not involved, and of those that are, almost all do not exclusively sell such solutions.

-The third case also concerns a minority of companies, and is an expensive and unsuitable solution for the time being. This means having our own natural carbon sinks to store the carbon we emit: peat bogs, forests, oceans.

-The final option is to offset emissions by financing projects that reduce other emissions or sequester carbon. This is the second secret weapon of companies that claim to have achieved, or want to achieve, carbon neutrality. But here again, the arithmetic doesn’t work, since the potential for reducing emissions in this way is at best half of the 37 Gigatonnes of annual GHG emissions generated by human activity. What’s more, the compensation system poses a number of problems that need to be addressed.

“Nature doesn’t make zeros

We can’t set a balance sheet against the complexity of nature and its ecosystems. In the logic of its advocates, a plus is worth a minus: a tree planted here offsets the CO2 emitted there. In reality, carbon is not absorbed at the same rate as it is emitted, and the damage caused by a human action is never fully offset by a positive action. How can we compensate for the destruction of an ecosystem, the extinction of a living species, pollution and its consequences on health?

The famous economist Kate Raworth expresses very well how out of touch this concept is with the reality of nature:

“Nature doesn’t do ‘zero'”… “Nature is generous, it sequesters carbon, it creates cycles. The idea of aiming for ‘zero’ doesn’t connect us to these living cycles of the world.”

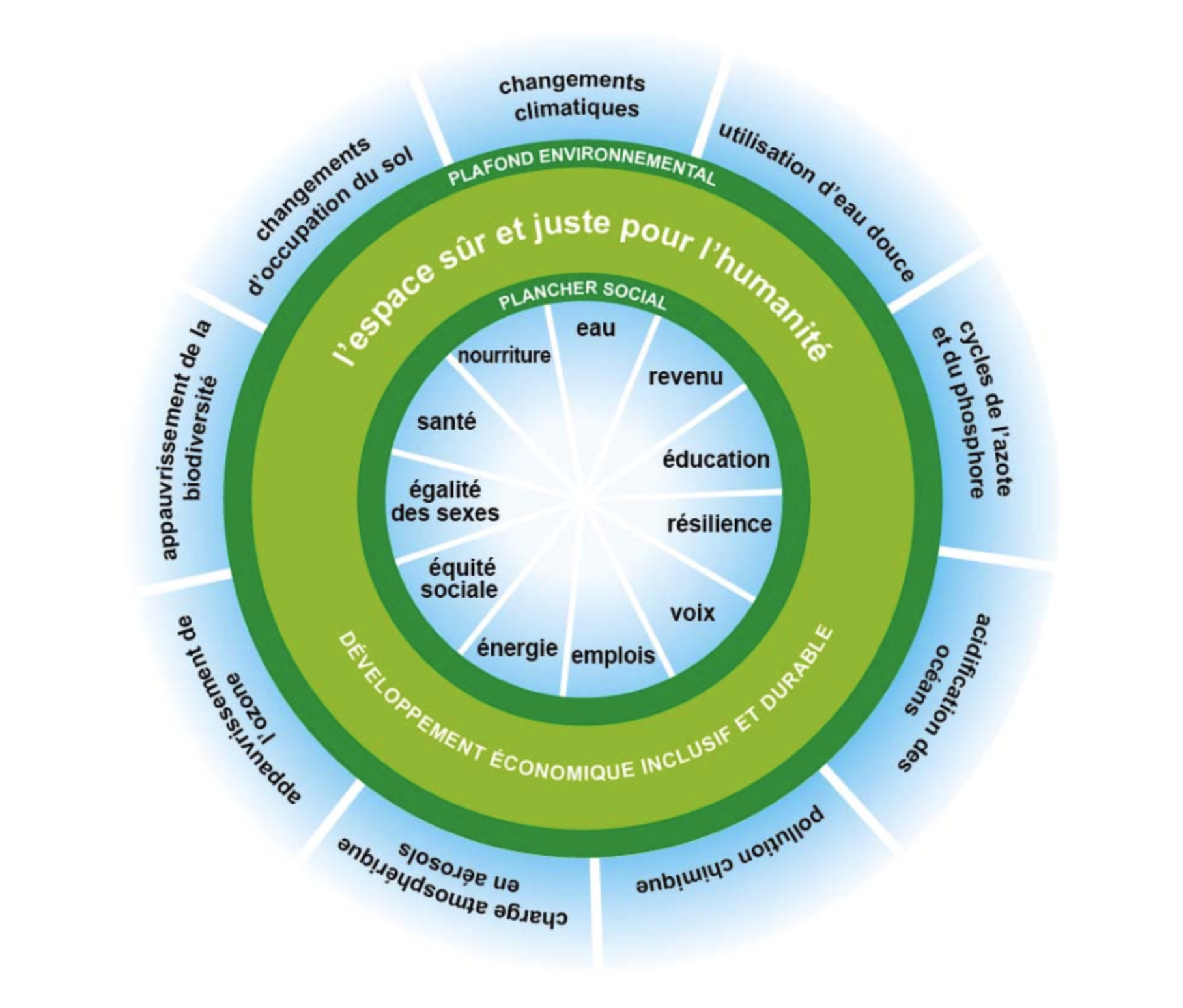

Kate Raworth developed the the doughnut economy , based on the principle that all economies must be situated between a social base (inspired by the UN’s Sustainable Development Goals – SDGs) and a social base (inspired by the UN’s Millennium Development Goals – MDGs). ODD) to ensure that no one in the world lacks the essentials, and an ecological ceiling to ensure that humanity does not collectively exceed the planetary limits (defined by Johan Rockström), which protect the Earth’s vital systems. This balance between an ecologically safe and socially just space is one in which humanity can thrive. It may be useful to recall that of the 9 planetary limits defined, six had already been exceeded by the end of last year.

Sequencing

The way in which companies approach offsetting in terms of sequencing and prioritization helps to put the urgency of acting on our footprint at source into perspective. Why tackle emissions reduction if you can become “carbon-neutral” with your hand in your pocket, and make your customers believe that consuming your products and services won’t exacerbate the climate crisis? Compensation must return to its rightful place in the sequence of actions to be undertaken to contribute to the ecological transition, i.e. the last one: 1.Avoid 2.Reduce 3.Compensate. Compensation must remain the last resort for damage that cannot be avoided or reduced.

Collateral damage

Most compensation programs are based on tree planting. As I’ve already mentioned, these compensation programs will only show their effects in 10, 20, 30 years or more, and we don’t have that much time. Planting trees is all very well, and we must continue to do it, and especially to do it well, but it must not be used as a veneer of environmental responsibility to justify inaction, as is all too often the case today. On the other hand, there are a certain number of problems that can be caused by conservation and reforestation programs, for example:

-Displacement of indigenous communities or restricted access to forests.

-According to the UN, 45% of the world’s planted forests are composed of one or two commercial tree species. The lack of distinction between native forests and commercial plantations can conceal the decline of the former and the advance of the latter, and thus pose a threat to biodiversity. What’s more, large-scale plantations can disrupt soil fertility and dry up rivers and lakes through water consumption.

Of course, forests have the capacity to store carbon, but we mustn’t forget that they also provide ecosystem services essential to all life on earth: regulating the water cycle, soil formation and protection against erosion, air purification, temperature regulation, pollination and pest control, as well as the cultural richness of the indigenous populations they shelter. Nature is a totally interconnected system, and we need to take this into account.

Ineffective or worse

A survey was conducted over a nine-month period by the Guardian, the German weekly Die Zeit and SourceMaterial, a non-profit investigative journalism organization, on Verra, the world’s leading carbon standard for the voluntary offset market (used by Disney, Shell, Gucci and other major companies). It reveals that over 90% of their rainforest offset credits – some of the most commonly used by companies – are likely to be “phantom credits” and do not represent genuine carbon reductions, or could even exacerbate global warming.

The point here is not to consign carbon offsetting to oblivion, but to put it back in its rightful place. In the latest part of the IPCC’s 6th report on global warming mitigation, the experts state that to avoid climate runaway, and in the face of emissions that have not fallen for decades, carbon offsetting (natural or artificial) will certainly have to be massively developed. Even if it is imperfect, it must nevertheless be an integral part of the ecological transition, provided it is effective and does not have negative consequences elsewhere.

When will this smokescreen of thinking that we can continue to live indefinitely according to this linear, extractive model dissipate and give way to a “net-positive” economy, as Kate Raworth calls it, a restorative and regenerative economy? When are we going to stop clinging to the technological solution at all costs, trying to create a new world? cloud of lunar dust in Earth orbit to attenuate solar radiation or develop solar geo-engineering to reflect solar radiation into space in order to limit global warming* to finally put human ingenuity and financial resources at the service of a truly viable and sustainable transition?

The real challenge today is above all to radically transform our production models and organizations in order to reduce our emissions at source, because to date there is virtually no company in a position to claim that its CO2 emissions are falling in absolute terms. Emissions need to fall by 5% a year for the next 30 years if we are to meet the target of limiting global warming to +1.5 degrees above pre-industrial levels, yet they continue to rise every year.

Between fatalism and solutionism, there is a third way, full of hope, which consists in urgently committing to a real transition, because the solutions and technologies for acceptable sobriety without regression do exist.

*Find out more about solar geoengineering: